The Struggle for Public Schools

A moral and strategic necessity

Public schools occupy a unique, important, and contradictory position in US society. They enshrine inequalities of race and class while also offering the potential to ameliorate and overcome them. They also have a varying but uniquely significant degree of direct democratic oversight in the form of elected school boards. They are important spaces for community events and public recreation, and are entrusted with developing and caring for the future of our families and species. They serve a key role in social reproduction, simultaneously functioning as sites of child care, workforce development, and—ideally—molding a curious and informed populace.

Consequently, public schools have long been important sites of political contestation. Black activists famously fought for school desegregation and overturned Jim Crow laws in the 1950s and 60s, but this victory has been slowly undone. Years of bipartisan neoliberal disinvestment and privatization have left US public schools overcrowded and in poor shape in many places, particularly poor, Black, and Brown neighborhoods, along with an often underpaid and overstressed workforce. And we now have seemingly regular school shootings, which bring not only horrifying direct violence but a nationwide cottage industry of traumatizing and useless school shooting drills and cops.

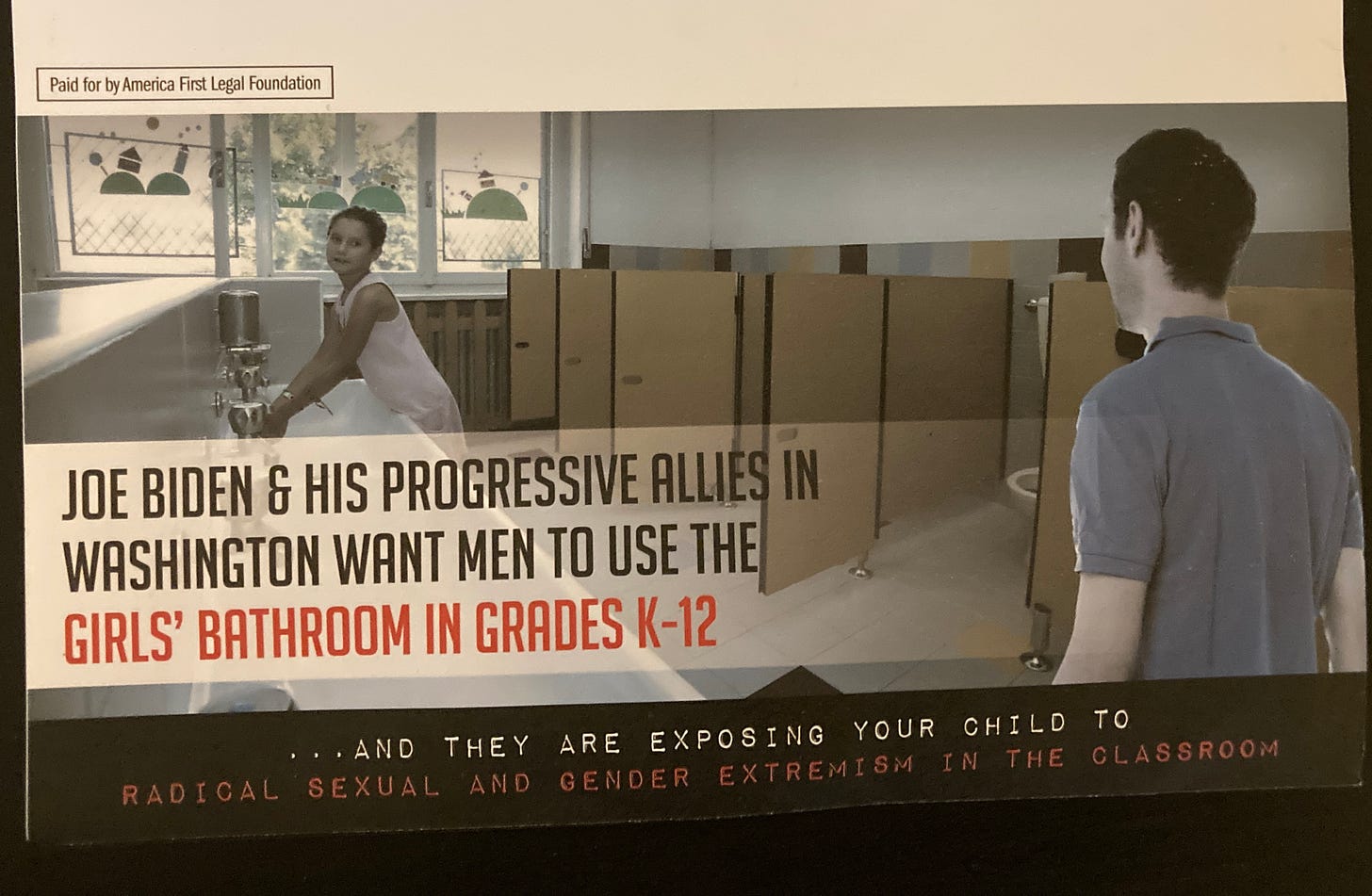

Then the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted and exacerbated trends of inequality in schools, with fights over necessary mitigation policies adding further fuel to the fire as the longstanding reactionary war on public education and teachers’ unions exploded with newfound ferocity. This has manifested in a malevolent moral panic with things like banning books, harassing and trying to take over school boards, attacking teachers, running racist and homophobic election ads, and enacting legislation to deny care to trans kids or stop the teaching of anything considered to even remotely promote racial justice or LGBTQ issues. At a recent rural Michigan school board meeting, local adults showed up to complain about and censor a pleasant and vibrant mural painted in their district’s middle school, going so far as to harass the teenage artist because of a trans flag and ridiculous claims of “Satanic” and “anti-Christian” imagery. In one particularly one on-the-nose example, a school board candidate in Nevada was inspired to run because his children were assigned to write about “sympathy” and “empathy.”

This is truly evil shit. And these trends have, understandably, led to an even more demoralized and shrunken workforce; the US has ”309,000 fewer teachers and school support staff” than we did in January 2020.

While obviously distressing, what does all this have to do with the environment? In a broad sense, the same systems of oppression that drive this malevolent force are the same that underlie the climate and ecological crisis. But to get a little more granular and specific, the public school system produces significant greenhouse gas emissions and serious environmental injustice—lead, asbestos, toxic mold, and other pollutants in the building air in addition to particulate matter from diesel school buses. This type of pollution is terrible for everyone’s health, but it is especially harmful to the developing minds and bodies of children. Relatedly, many public schools also lack adequate heating and/or cooling, which due to global warming is an increasingly salient issue that impedes their ability to function.

And because public schools are public, they offer the means to start making the sorts of social, political, ecological, and physical transformation we need. For example, schools across the country have been investing in solar panels and retrofitting and using the huge savings in energy bills to increase teachers’ salaries. Robust federal action, like the $140 billion per year proposed in a recent Climate and Community Project (CCP) report (disclosure: I am currently a Research Fellow with CCP), would help a great deal, particularly for ameliorating funding inequities across districts. Unfortunately, nothing of that scale is on the table right now due to the ideological composition and structural impediments of the federal government, as evidenced by the lack of movement on the Green New Deal for Public Schools legislation based on CCP’s research.

Winning transformative changes to the public school system—and society more broadly—will require building power at the local level, and DSA members in Austin, Philadelphia, and Los Angeles are doing just that.

Austin

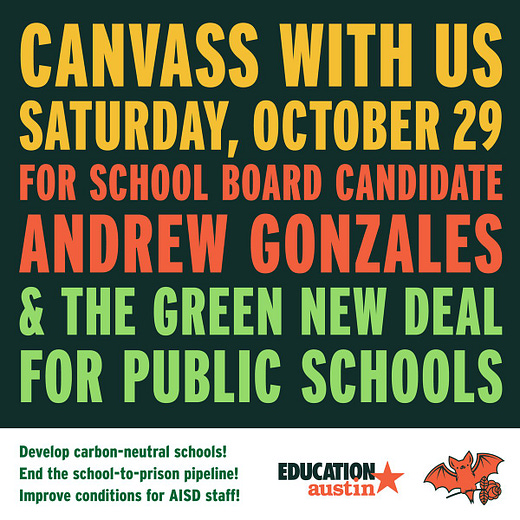

Austin teachers have been busy fighting for basic worker safety protections alongside dealing with overheated classrooms, which has myriad negative effects like causing hearing aids to malfunction and making it harder for students to focus. So Austin DSA’s Green New Deal for Public Schools campaign has been working with Education Austin, the local teachers’ union, and the Texas Climate Jobs Project (TCJP), a coalition of unions fighting for a just transition in Texas.

Schools are a core part of TCJP’s agenda—namely, electrifying the school bus fleet and retrofitting and installing solar panels on public schools. The chapter has a number of union members among their ranks, and they have built good relationships with organized labor by demonstrating solidarity through this campaign.

Right now, the coalition’s focus is changing the composition of their local school board, the Austin Independent School District (ISD) Board of Trustees, because Education Austin has seen their priorities repeatedly fail against a hostile board. There is a slate of progressive, pro-union candidates running, and Austin DSA has endorsed one of them in particular: Andrew Gonzales. So for the time being, Austin DSA is focusing their campaign on working to get Gonzales elected.

Philadelphia

The pandemic has brought newfound attention to the importance of indoor air quality and ventilation. Philly DSA worked with parents and students to purchase and utilize carbon dioxide monitors that showed alarmingly poor air quality in schools they measured—high levels of carbon dioxide are detrimental for cognitive functioning and are indicative of poor ventilation in general. That is why Philly DSA is running a Safe Air for Philly Schools campaign.

They have been partnering with teachers, parents, and students to build Corsi-Rosenthal boxes, which are do-it-yourself air purifier machines made from a fan, a few air filters, and some cardboard and duct tape. These cheap and easily assembled boxes are remarkably effective at filtering air.

While making Corsi-Rosenthal boxes is a useful tactic for mitigating air pollution and building relationships in the community, organizers understand it is a limited, short-term solution. So Philly DSA is also circulating a petition with broader demands for The School District of Philadelphia to conduct a district-wide assessment of school ventilation systems alongside providing Corsi-Rosenthal boxes for every classroom in the short term and upgrading all the HVAC (heating, ventilation, and air conditioning) systems in the medium term. As one Philly DSA organizer recently testified, the District can use newly available funds from the Inflation Reduction Act for electric heat pumps to both cut their reliance on fossil gas and improve HVAC systems, which is true for other school districts as well.

Los Angeles

The LA Unified School District (LAUSD) is the largest consumer of energy in LA County, which offers an important opportunity to mitigate the climate crisis and create a more just and equitable school system. DSA LA’s Green New Deal for Public Schools campaign has five core demands for the LAUSD Board of Education: installing solar panels on school rooftops, extending a free public transit pass program, expanding green spaces and community resources, establishing a climate-based curriculum, and electrifying the school bus fleet.

The chapter is advancing these demands in two ways. The first is directly through the school board. They are working with a coalition of local groups to pass a resolution to create a dedicated office for sustainability and climate justice, which is a way to build actual public sector capacity rather than continuing the neoliberal practice of farming important work out to nonprofits or consultants. They are also supporting Dr. Rocio Rivas for the LAUSD School Board (alongside a couple City Council candidates). On the doors, climate change is a big issue for people, and organizers can easily make connections to more and better jobs and better conditions in their schools. If Rovas wins, she would tilt the balance of the school board from the current majority in favor of privatization to one that is fully supportive of public education and public investment.

The second aspect of the campaign is supporting the United Teachers of LA (UTLA), the local teachers’ union, with their current contract negotiations. UTLA is a progressive union that takes a “bargaining for the common good” approach, soliciting community input on what they should fight for in their new contract in order to build a broad coalition of support. DSA LA got involved in this process early on, having built a strong relationship with UTLA since supporting their 2019 strike. Organizers working on the campaign feel that winning demands through the UTLA contract could be stronger than through a school board resolution, given that the latter can pass then fall to the wayside. Unfortunately, LAUSD is currently refusing to bargain on the more expansive demands, only salary and benefits. But UTLA has won demands like these before, and doing so again will take the sort of multi-faceted community pressure that this approach is designed to foster.

After next week’s election, DSA LA plans to shift their GND campaign focus towards base-building, reaching out to the people they talked to while canvassing around public schools in order to bring them into the campaign and build deeper relationships.

As these examples show, public schools offer a strategic opportunity to combine and connect different types of tactics—electoral, labor, mutual aid, etc.—and different types of people and groups around the common good and build muscle for bigger fights to come. For example, school board elections are very winnable for an organized group, and they can be a springboard for winning campaigns for higher elected offices.

These campaigns also offer an opportunity to make connections with and between organized labor and the communities they inhabit. Teachers’ unions are some of the most militant and progressive in the country, leading the way on bargaining for the common good and often endorsing left campaigns and candidates, and teaching is an important sector of “pink-collar” workers the likes of which are undervalued in the present state of things but are vital for a care-and-repair-based society. Greening our public schools will require a great deal of labor from building trades as well, including electricians, roofers, construction workers, and more.

For these reasons and more, public schools are vital places of struggle right now. We must defeat the revanchist, Christo-fascist movement that is trying to take over not only schools, but the entire country. Instead, we can win just and sustainable public schools that are community building blocks for the world we need. Class struggle is in session.