Raj Patel on agroecology, reparative approaches, and land reform

"Agroecology is a way of understanding how to grow things, but also understanding that agriculture doesn't just happen in fields."

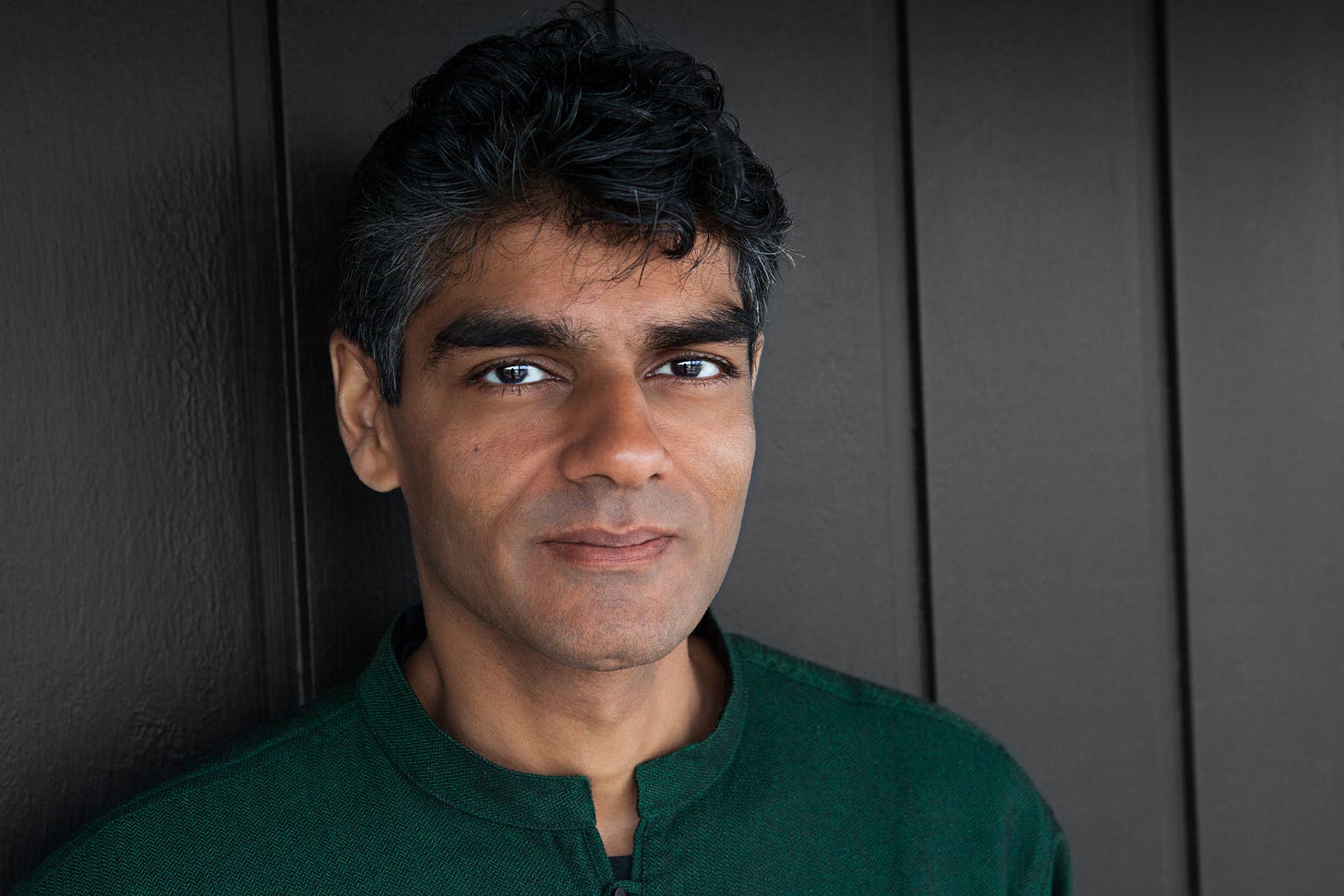

Raj Patel is an award-winning author, film-maker and academic. He is a Research Professor in the Lyndon B Johnson School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas, Austin. In addition to scholarly publications in economics, philosophy, politics and public health journals, he regularly writes for The Guardian, and has contributed to the Financial Times, Los Angeles Times, New York Times, Times of India, The San Francisco Chronicle, The Mail on Sunday, and The Observer.

His acclaimed latest book, co-authored with Rupa Marya, is entitled Inflamed: Deep Medicine and The Anatomy of Injustice. His first film, co-directed with Zak Piper and filmed over the course of a decade in Malawi and the United States, is the award-winning documentary The Ants & The Grasshopper. He can be heard co-hosting the food politics podcast The Secret Ingredient with Mother Jones’ Tom Philpott, and KUT’s Rebecca McInroy.

This interview has been edited for content and clarity.

Matt: As you discuss and show in your work, we have a deeply unjust and unsustainable food system in myriad ways that exploits human and nonhuman nature all around the world, driven by profit accumulation. Why is agroecology the solution to that?

Raj: To understand why agroecology might be the solution to that, you need to understand what agroecology is. Agroecology is a way of understanding how to grow things, but also understanding that agriculture doesn't just happen in fields. Agriculture is the product of a range of operations of social power, and that's really hard for people to get their heads around. I think that it speaks to the success of capitalist agriculture that we believe that what happens in fields is agriculture, but what happens at the Department of Agriculture isn't agriculture, that's something else. Even though it says “Agriculture” in the fucking title, we refuse to accept that that's actually agriculture. That's policy, policy doesn't have anything to do with agriculture—except that it is agricultural policy. It just takes so much work to really mount an effective counter-hegemony to the common sense understanding of how agriculture operates.

So you need to understand industrial agriculture is itself the product of centuries of colonialism, the normalization of certain operations of power on the land, genocide, histories of enslavement, and then centuries on top of that of just paying workers in the food system shittily. It is normal in the United States that seven out of the 10 worst-paying jobs in this country are in the food system. It is normal because there is a history of that always being the case as long as this country has had its name. If you understand that that's what agriculture is—the operations in the field are intimately connected to these other kinds of histories—then you need to understand that the opposite of that would be something that involved land reform, it would be something that understood and valued labor, that understood and valued biodiversity.

What we have in our operation of agriculture at the moment is a very conscious idea that we ought to render almost everything extinct in the fields except one or two things which we quite like. The way that modern agriculture works is by annihilating all kinds of life except the life that is profitable. That profitable life looks like a monoculture. It looks like there's one crop coming out of the ground and that's the crop that we're harvesting, even if that crop itself is dependent on multitudes beneath the soil and is dependent on cheap labor and is dependent on a range of other trails of operations of power and life off the field. What is immediately visible is just the one crop. The opposite of that is a recognition that actually you need a vast range of life above and below the soil and in and around the field in order to be able to sustain a vibrant ecosystem. Rather than having one crop, agroecology generally looks for polyculture and looks to build soil fertility and looks to sequester carbon in the soil. Not because it's lucrative, but because it is a way of maintaining a robust and viable ecosystem for the future.

So it's not that agroecology is just very sophisticated organic farming. In fact, you can have industrial organic farming, you can have just the one crop being grown in industrial methods. In China, for example, the way that organic strawberries are grown is basically with miles and miles of plastic on the ground. Yes, you get your organic strawberries because you haven't added pesticides to it, but it is still very much a monoculture driven by the machinations of capitalist agriculture. Agroecology is a way of understanding farming that can break with the idea that we farm under the aspect of for-profit agriculture, but that's not always the case. Agroecology can happen for profit, agroecology can happen in ways that are exploitative, particularly of labor. It's possible to do agroecology without thinking too hard about land reform, and that's the kind of agroecology we see predominantly in India, for instance.

I think that there is a horizon under which agroecology can operate that doesn't ask some of the very hard questions that socialists, for example, would want to ask. What is the mechanism under which this land is placed under democratic control? What are the mechanisms under which labor is respected and rewarded in ways that are not exploitative? What are the ways that we see gender equality play out in the operations of this kind of agriculture? To do good agroecology in ways that are consonant with democratic socialism, for instance, you would need to ask questions about control over land and control over the division of productive and reproductive labor. Those questions often—but not always—feature in agroecological approaches.

There's a certain tendency that you see on the Left, you could call it ecomodernist, that sees industrial agriculture as good and necessary; we just need to democratize it or socialize it and take the reins. So they might see agroecology as backwards and even repeat Green Revolution talking points. What is wrong with that idea? And what do you say when you encounter people like that?

Well, I'm curious why the Sixth Extinction doesn't matter for communists. I think it should. It's entirely possible to have social control over that and still end up annihilating the planet if we don't recognize the importance of robust and diverse ecosystems. We still need to live in some sort of recognition that humans can't hive themselves off into cities and pretend that nature happens outside the city, and inside the city is some fantastically controlled biome over which humans have dominion. That's not the way that the planet or ecology works. We've got plenty of evidence now that suggests that the rise of inflammatory disease lies precisely in humans believing that we ought to just bleach our way out of anything and everything that we don't like. What we see as a result is the rise of certain kinds of diseases that are associated with a lack of biodiversity within our own microbiomes. I'm not seeing any plans for bioreactors that address or acknowledge in any way the vital importance of a robust microbiome.

If the charge is happening under the red flag, then it's important to recognize how much fucking communist and socialist activity is happening on the land. You don't get to be the person who champions bioreactors for the people, but at the same time waves away all the Marxist activity that's happening on, in, and around the land in the name of and by workers who are every bit as communist as the communists who have the “Nothing's too good for the working class” bumper stickers on their cars. A bit of solidarity would be nice to have from our comrades who are pushing this ecomodernist approach that seems to me functionally indistinguishable from what the capitalists are pushing.

Yeah, I totally agree with that. So an agroecological food system would require more human labor because you're replacing fossil fuel inputs and things like that, and that's often presented as a serious detriment because farm work can be very onerous, especially under our current system. But I don't know if that's necessarily a bad thing. People garden in our spare time, there's increasing interest in farming among young people, so I feel like people feel alienated from our ecology and where our food comes from. What do you think about the idea that we will need more people in agriculture, and the challenge and promise in that?

It's certainly the case that industrial agriculture has for centuries been trying to maximize profit. When workers push back against that, then capitalists replace labor with machines, with chemistry, and with a range of technologies that seek both to steal from the worker and from a range of knowledge producers’ ideas about how to farm, but without ever paying for that. And to steal from future generations the possibility of a viable planet, but to do it in a way that maximizes profit by essentially kicking workers off the land.

Now after centuries of having successfully gotten rid of workers, we find ourselves needing an agriculture that brings them back again. This is used as an argument against agroecology, and I get where that's coming from. But, as you say, some of the benefits accrue directly to the workers whose bodies are rendered more resilient and more diverse through their connections with a vibrant ecosystem and through the dirt under their fingernails. We've got lots of data to suggest that folk who grow up and work on farms that are rich in agroecological practices have less in the way of inflammatory diseases than those who are either not exposed to soil or are exposed to the industrial chemicals that are part of the modern food system.

I think it's okay to say, “Yes, there will be a need for more labor in food systems,” and then also to say, “And that's why we need to pay workers better up and down the food system so that we recognize the vital value of knowledge that's brought to agriculture.” Because at the moment, the cheap farm labor in the United States is usually migrant farm labor, and that farm labor has been trained in farmwork over decades and generations. There's a lot of expertise that is required even for industrial agriculture, and that's usually coming from farmers and farmworkers who've been working the land for generations south of the border. Is it right that we should be paying for that? Absolutely. A potential dividend of a shift towards agroecology is a recognition not only of the imperial character of American farming even today and the need to engage in reparations for the destruction of agriculture south of the border, but also a recognition of the deep knowledge and work that is required to make agriculture possible. So is it going to be more expensive? Yes, and it should be because cheap food has been bought at the expense of the planet and of workers for far too long.

When people think about what sort of food system we should be moving to, you hear centralization versus decentralization, or globalization versus localization. These are often presented as binaries. What do you think about those ideas and how we should think about them when it comes to food?

You're absolutely right, Matt, that they are presented as these polar opposites. I think the axes and the dimensions of this question are dictated by a kind of liberalism/anti-liberalism rather than along axes of socialism. This kind of approach to thinking about “is local better or is international better?” ignores a couple of things. First of all, it ignores colonialism and the embedded histories of why it is that certain parts of the world only have the choice of growing tropical products or nothing. Understanding that before we start deciding whether we want chocolate or not or whether we want bananas or not, how about we engage in reparations for the disruption that has been wrought on large parts of the Caribbean, West Africa, or Southeast Asia where our tropical products that we depend on come from. Engage in a process of a solidarity economy of reparations in order that working people there get to decide what it is that they would like to do with their lives rather than be faced with the choice of Fair Trade or nothing.

Beyond that, I do think that it's important for us to re-localize our food systems, but to do it in a way that recognizes the interdependencies of our diet and of the world in which we find ourselves. I certainly think reparative approaches to the way the Global North has treated the Global South is important, but also reparative approaches to the way that the modern food system has treated working class communities in the United States. We've seen the ways that frontline communities were required to sacrifice themselves in order that we continue to have cheap meat or conveniently delivered groceries under COVID. It was the working class, it was predominantly people of color; in the meat industry, it's disproportionately people of color and women on the production lines. They were required to be sacrificed so that the middle class could enjoy a stable and recognizable food system. That can't endure.

So I do think that a better food system is one that operates in a sophisticated way of recognizing that not all food is going to come from within 10 yards of where you live, but recognizing that it is possible to have local and regional hubs to aggregate food supplies then redistribute them. To recognize that we are going to have to change our diets, and that's okay. That means having less meat, and in general that doesn't go down well in the United States, but it's going to have to.

And also understanding that some of the most exciting food systems, for example in Cuba, happen not because the government decides this is what it's going to be, but because peasants rise up and make the government bend to the people's will. The way that Cuba was able to have a thriving agroecological food system was not because the government was naturally inclined that way; the Government of Cuba wanted after the Special Period to just embrace more chemical fertilizer and monoculture in the way that it had been taught by the Soviet Union. It was peasant movements in Cuba that redeployed the army of PhDs in agriculture to develop a very robust and science-informed agroecological food system where there was some food growing in cities, some in the peri-urban area, and some in the rural area. It was aggregated in a way that was robust enough to make sure that nobody starved. That's an important policy.

Similarly, in Brazil, one of my favorite examples there is the city of Belo Horizonte, where a range of policies emerged essentially through worker organizing. PT, the Workers' Party there, had lots of grassroots organizing to be able to end hunger in that city. While Bolsonaro has managed to eviscerate a great deal of that policy, I'm hoping that a resurgent Lula regime might be able to bring that back. In all of these cases, what's interesting is not the choice between local or international, but more about how much of this is driven by the grassroots and driven by workers’ organizations and organizations that understand the vital importance of a connection to the land.

What lessons do you think that people here in the US fighting for agroecology can take from successful movements in the Global South like you were talking about? And with that, maybe relationships of solidarity that can be built.

It's a difficult question in the United States, because what movements in Cuba and Brazil are very acutely aware of is the need to have a conversation and transformation in the way that property is held, that private property is held in particular. And access to agricultural land is made possible by local, municipal, state, and national government. That's a hard sell in the United States; talking about land reform here is very difficult.

I gave a talk to a Republican men's group recently, which is a very odd thing for me to be doing. It went as badly as you would expect, except for the bit where we realized that we all hated Bill Gates, and we hated him for similar reasons. There were some who hated him because he was injecting them with chips through his control of the vaccine supply, but in general, people didn't like that he was so powerful and that he was the largest farmland owner in the United States, for instance. There was something suspicious about that, even for Republicans. The idea that so much land can be concentrated in the hands of so few, whether it is Bill Gates or whether it's Wall Street investment vehicles, is prompting at least a flicker of concern from those who would like to imagine America being a heartland of small family farms. America has never really been that, but the myth persists. Insofar as that myth is useful for mobilizing for an actual American future that recognizes stolen land and the history of enslavement, and also recognizes the possibility for cooperatively run and managed invitations to Indigenous land, I think that there's something quite exciting there.

So the idea of property reform and land reform in the United States is a difficult process. If we're thinking about solidarity there, that's a long road to hoe. But we should do it! And La Via Campesina’s more radical members, particularly in Brazil, are ones to whom to look, I think. There are examples of worker organizing really addressing the key issue of hunger and thinking about labor. Bread and butter issues are always labor issues. Understanding how food systems are not just about the theft of labor, but also about the nourishing of communities offers a way of breaking open a purely workerist approach to understanding how transformation might happen. Although I'm a fan of workerism, I also recognize that you can't overlook how vital reproductive labor is to the success of the modern food system. For whatever food system comes after it, we will need to be organizing in ways that are feminist and that recognize the vital importance of shared and solidaristic approaches to reproductive labor. So all of that we can learn from our comrades in places like Brazil and in Cuba. And I think it's always important to recognize that in all of these cases, even when it appears that we've been in control of the state, we've never been in control of the state. I think an attitude of permanent opposition, even to our comrades who find themselves in government, is really quite important.

Even when the Left seizes power, you still need people pushing outside.

Yeah, I think that was one of the disappointments of the Lula administration, that the MST stood down a little bit and the number of land occupations went down. That meant that after the Lula administration, in that transition into Bolsonaro, the movement was substantially weaker. Movement building doesn't stop when you have your guy in power. In fact, that's a reason to actually ramp it up. That's a mistake that was obviously made in the United States by people who thought that Obama would bring peace and joy and love. That mobilization doesn't stop, and it's really difficult to sustain. What's it like to do this for a lifetime? Well, we're going to find out because that's absolutely what we're going to need; if we let up even for a minute, the Right wins.

So how are you thinking about the present political moment, especially here in the US, and what to do about it?

I'm as “pessimistic of the intellect” as anyone of the United States. You've got a Supreme Court that's handing out candy to corporations and to the Religious Right. This is a white supremacist organization that's very happy to reimagine a sort of Gilead for capital in the United States. I don't think that there are many augurs of success for a Green New Deal in agriculture. Even if you look at what's being discussed in Congress right now in terms of voluntary credits for carbon sequestration, it's a travesty. There's very little that I can look at in the current configuration of forces and not feel quite depressed about.

But that's why we organize. I'm still heartened by the fact that there are many people who have populist ideas, and populist in that sense of recognizing that the working class has much more in common than elites would like us to think and that the overthrow of Wall Street is something that we ought to be organizing towards. That was true in 1893, and it's true now. There are moments of populist organizing and deep organizing happening in the United States that I think are hopeful, but it's definitely candles in a very dark time. But what's the alternative? Just shrug and walk home? No. Even though these are very dark times, the increasing interest in socialism from the young is something not to give up on. And the rise of certain kinds of candidates who understand and can articulate that, like Austin's very own Greg Casar, for instance—if you haven't heard of him, you'll be hearing of him soon. All of that gives me a great deal of hope.